The Life of Salvador Dalí

Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech was born at 8:45 on the morning of May 11, 1904 in the small agricultural town of Figueras, Spain. One year earlier his brother - also called Salvador - had died at the age of seven from an attack of meningitis.

Salvador Felipe Jacinto was the son of the prosperous lawyer and notary Salvador Dalí y Cusi from Cadaqués, Gerona and Felipa Domènech Ferres from Barcelona. He spent his childhood in Figueras and Cadaqués where his parents built his first studio. At an early age, Salvador was producing highly sophisticated drawings, and both his parents strongly supported his talent.

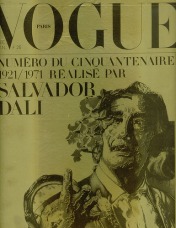

In 1914, the young Salvador Dalí attended a private painting school and in 1918, at the age of 14, he had his first exhibition in the Teatro Municipal in Figueras which is now converted into the Teatro Museo Dalí.

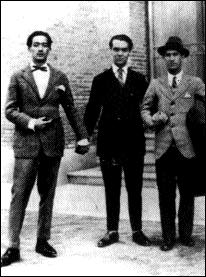

In 1921, Dalí attended the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid and lived in the Residencia de Estudiantes where he met the poet Federico García Lorca and the filmmaker Luis Buñuel. The three artists developed a very special friendship which influenced their lives. In the early 1920s, Dalí experimented with Cubism and Metaphysics and exhibited paintings in student art shows.

Dalí had been very eccentric since his childhood, wearing long hair and sideburns, and dressing in the style of English Aesthetes of the late 19th century. For criticizing his teachers and allegedly starting a riot among the students he was suspended from the Academy in 1923. He returned to the Academy in 1926, but was permanently expelled shortly before his final exams for declaring that no one in the faculty was competent enough to examine him.

In 1927, he visited Joan Miró in Brussels and Pablo Picasso in Paris, where he experienced a great emotion when received by the Artist. He showed his respect and said "I have come to see you before visiting the Louvre" and Picasso responded "You have done right indeed".

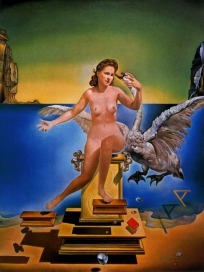

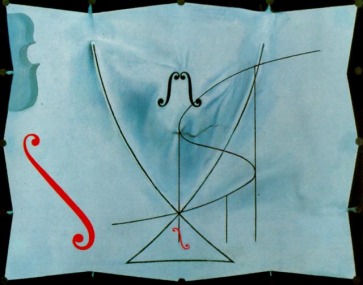

On Dalí's second visit to Paris, in 1928, Miró introduced him to the Dadaist and Surrealist Group, including the surrealist writer Paul Élouard and the painter René Magritte. By this time, Dalí was working with Impressionism, Futurism, and Cubism. Dalí's paintings became associated with three general themes: depicting a measure of man's universe and his sensations, the use of collage, and objects charged with sexual symbolism and ideographic imagery.

All this experimentation led to Dalí's first Surrealistic period in 1929. These oil paintings were small collages of his dream images. His work employed a meticulous classical technique, influenced by Renaissance artists, that contradicted the "unreal dream" space he created with strange hallucinatory characters. Even before this period of his art, Dalí was an avid reader of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theories.

Dalí's major contribution to the Surrealist Movement was what he called the "paranoiac-critical method", a mental exercise of accessing the subconscious to enhance artistic creativity. Dalí would use the method to create a reality from his dreams and subconscious thoughts, thus mentally changing reality to what he wanted it to be and not necessarily what it was. For Dalí, it became a way of life.

1929 was also the year when Dalí expanded his artistic exploration into the world of film-making when he collaborated with Luis Buñuel on two films, Un Chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog), which is well remembered for its opening scene of the simulated slashing of a human eye with a razor, and in 1930, L'Age d'or (The Golden Age), which caused a scandal and was finally banned.

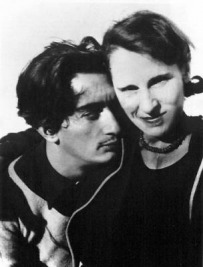

In the same year he met Elena Dmitrievna Diakonova, a Russian immigrant and the wife of Paul Élouard. A strong mental and physical attraction developed between Dalí and Diakonova, and she soon left Eluard to spend her life with Dalí. Also known as Gala, she became Dalí's muse, inspiration, and eventually his wife. She helped balance, or one might say counterbalance, the creative forces in Dalí's life. With his wild expressions and fantasies, he was not capable of dealing with the business side of being an artist. Gala took care of his legal and financial matters, and negotiated contracts with dealers and exhibition promoters. They were married in a civil ceremony in 1934.

By 1930, Salvador Dalí had become a notorious figure in the Surrealist movement. One of Dalí's most famous paintings produced at this time—and perhaps the best-known Surrealist work—was The Persistence of Memory (1931). The painting, sometimes called Soft Watches, shows melting pocket watches in a landscape setting resembling that of Cadaqués. It is said that the painting conveys several ideas within the image, chiefly that time is not rigid and everything is destructible.

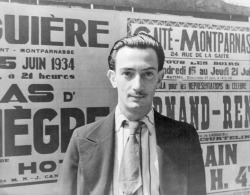

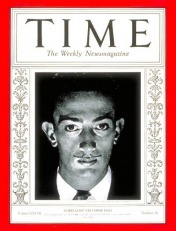

By the mid-1930s, Salvador Dalí had become as notorious for his colorful personality as for his artwork and, for some art critics, the former was overshadowing the latter. Often sporting an exaggeratedly long mustache,cape, and walking stick, Dalí's public appearances exhibited some unusual behavior.

As war approached in Europe, specifically in Spain, Salvador clashed with members of the Surrealist movement. In a "trial" held in 1934, he was expelled from the group. There is controversy about the reason for his expulsion, some critics say it was due to his support of the subsequent Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, others maintain that Dalí "had repeatedly been guilty of counter-revolutionary activity involving the celebration of fascism under Hitler." It is also very likely that many members of the movement were aghast at some of his public antics. However, some art historians believe the expulsion was driven more by his feud with the movement's leader André Breton.

Nevertheless, he continued to participate in several international Surrealist exhibitions until the 1940s. During the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) he had to flee from Spain and lived in exile in several European countries, like Italy and France. In 1938, he met the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, who influenced his work significantly. Becoming more and more egocentric, Dalí drifted away from the Surrealist movement, asserting: „Le Surrealisme - c'est moi!“

During World War II, Dalí and Gala moved to the United States, where he had many exhibitions, publicated his famous fictionalized autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, designed costumes and sets for ballets and began his classic era. During this period he worked together with Alfred Hitchcock and Walt Disney.

Nevertheless, he continued to participate in several international Surrealist exhibitions until the 1940s. During the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) he had to flee from Spain and lived in exile in several European countries, like Italy and France. In 1938, he met the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, who influenced his work significantly. Becoming more and more egocentric, Dalí drifted away from the Surrealist movement, asserting: „Le Surrealisme - c'est moi!“

During World War II, Dalí and Gala moved to the United States, where he had many exhibitions, publicated his famous fictionalized autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, designed costumes and sets for ballets and began his classic era. During this period he worked together with Alfred Hitchcock and Walt Disney.

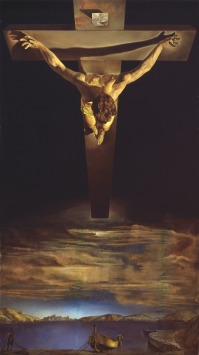

Dalí returned to Spain in 1948 and began his period of “Nuclear Mysticism“. Over the next 15 years he painted 19 large canvases, concerning scientific, historical or religious themes. During this period, his artwork took on a technical brilliance combining meticulous detail with fantastic and limitless imagination. He would incorporate optical illusions, holography, and geometry within his paintings. Many of his works contained images that depict divine geometry, the DNA, the Hyper Cube, and religious themes of Chastity.

In 1958, Dalí and Gala met the Pope and were subsequently married once again, but this time in a religious ceremony.

In 1964, Dalí awarded one of Spain’s highest decorations, the Grand Cross of Isabella the Catholic. The Asian art market began to be interested in Dalí's work exhibiting his paintings in Tokyo.

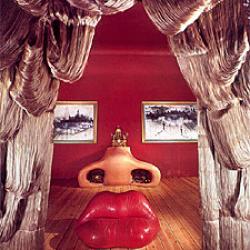

In 1974, the “Dalí Teatro-Museo“ in Figueras was inaugurated. The museum was the former Municipal Theater where Dalí had had his public exhibition at the age of fourteen. The original 19th century structure had been destroyed at the end of the Spanish Civil War. The new structure, formed from the ruins of the old, was based on Dalí's design. The museum is billed as the World's largest Surrealist structure, containing a series of spaces that form a single artistic object where each element is an inextricable part of the whole. The museum houses the broadest range of works by the artist from his earliest artistic experiences to works of the last years of this life. Several works on permanent display were created expressly for the museum.

In 1980, Dalí was forced to retire from painting due to a motor disorder that caused permanent trembling and weakness in his hands. He was not able to hold a paint brush, and lost the ability to express himself in the way he knew best. Then in 1982, his beloved wife and friend, Gala, died. The two events put him in a deep depression. He moved to Púbol, in a castle he had purchased and remodeled for Gala, possibly to hide from the public or, as some speculate, to die.

In 1983, Dalí painted his last picture, The Swallowtail. In 1984, he was severely burned in a fire, which confined him to a wheelchair. Friends, patrons, and fellow artists rescued him from the castle and returned him to Figueras, making him comfortable in his Teatro-Museo.

In 1986, Dalí allowed photographer Helmut Newton from Vanity Fair magazine to photograph him in a satin gown. He wore the Grad Cross of Isabella the Catholic and displayed the tube in his nose, through which he had been fed for over four years due to a psychological problem with swallowing.

In November 1988, Salvador Dalí entered the hospital with a failing heart. After a brief convalescence, he returned to the Teatro-Museo. On January 23, 1989, he died of heart failure at the age of 84. He is buried in the theater-museum's crypt, bringing his life in the world of art full circle. The Teatro-Museo had been built on the site where he had his first art exhibit, across the street from the church of Sant Pere where he was baptized, received his first communion, and his funeral was held. It's also three blocks from the house where he was born.

As an artist, Salvador Dalí was not limited to a particular style or media. The body of his work, from early impressionist paintings through his transitional surrealist works, and into his classical period, reveals a constantly growing and evolving artist. Dalí worked in all media, leaving behind a wealth of oils, watercolors, drawings, graphics, and sculptures, films, photographs, performance pieces, jewels and objects of all descriptions. As important, he left for posterity the permission to explore all aspects of one’s own life and to give them artistic expression.

Whether working from pure inspiration or on a commissioned illustration, Dalí's matchless insight and symbolic complexity are apparent. Above all, Dalí was a superb draftsman. His excellence as a creative artist will always set a standard for the art of the twentieth century.