Dalí the Cineast

The Surrealists expressed their ideas not only in the forms of literature and in painting, but also in films. In 1929 and 1930, Dalí collaborated with his friend, the famous Spanish film-maker Luis Buñuel, in the production of two surrealist movies. Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) and L'Âge d'Or (The Golden Age).

An Andalusian Dog (1929)

This surrealist mute filmlet of about 17 minutes was, according to Dalí, a product of two dreams by Buñuel and Dalí. Buñuel had dreamed about an eye that was cut by a razor, and Dalí had dreamed about ants swarming in the palms of his hands. The film was originally completely mute, but in 1960 music from Richard Wagner's Tristan and Isolde and a tango was added.

An Andalusian Dog is considered the most significant film of surrealist cinema. Violating the canonic narrative schemes, the film tries to provoke a moral impact in the viewer, with the help of extremely aggressive images. The first scene, for example, shows a woman whose eye is being cut by a razor. The film constantly refers to deliria and dreams, both in the produced images and in the use of time, which is not at all chronological.

Dalí and Buñuel wrote the screenplay for the film in less than one week, following only one quite simple rule: not accepting any images or ideas that could give reason to any rational, psychological or cultural explanation.

Themes, Motives, Techniques

The themes, motives and techniques of the film are mainly those that the surrealists were interested in, above all psychoanalysis. Buñuel and Dalí found a very irrational way to concatenate them, which makes the movie so interesting and compelling. They can be summarized as follows:

- superposition of images

- analogies

- paranoiac-critical method

- automatism

- irrational time and space

- passionate and impulsive love

- fetishism

- androgyny

- sadism

- sexual harassment

- split personality

- dominant father

- death and decay

- a box full of mysteries and secrets

Characteristic Scenes of the Film

There is no real structure or argument in An Andalusian Dog. The various scenes are not logically connected to each other. Therefore, it does not make sense to interprete the film as a whole, but only to have a closer look at some of the scenes and images.

The cut eye:

- the two most often anaylzed film minutes in the history of cinema

- icon of surrealism

- an initial shock which is preserved for the whole course of the film

- could be interpreted as a negation of the visual and the rational

The decomposed donkeys:

- the surrealist image of decay

- based on a painting by Dalí, called The Putrefied Donkey (1928)

Ants coming out of a hand

- typical dalinian image in his painting and writing (Dalí was afraid of ants)

- again the image of decay and death

- fascinating and horrifying at the same time

The mouth covered with the woman's axillary hair and the sea urchin

- perverse and perturbing sexual tension

- typically dalinian: the combination of completely unrelated images

The priests pulled by the cyclist

- the scene where the cyclist pulls the carpet with the pianos, the donkeys and the priests serves to illustrate the heavy weight of education and the bourgeoisie

- due to the weight the man cannot reach the woman, the object of his sexual desires

- education and the bourgeoisie impede the consummation of the sexual instinct

Following, you can watch the filmlet in two parts:

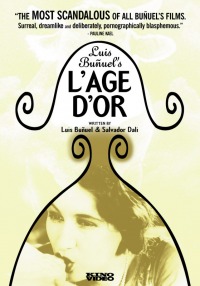

The Golden Age (1930)

Reception

The second surrealist film that emerged from the collaboration of Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, L'Âge d'Or (The Golden Age), caused a scandal. Buñuel only received the permission to show it because he said it was a dream of a madman.

On 3 December 1930, a group of incensed members of the fascist League of Patriots threw ink at the screen, assaulted members of the audience, and destroyed art works by Dalí, Joan Miró, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy and others on display in the lobby. On 10 December, the Prefect of Police of Paris, Jean Chiappe, arranged to have the film banned after the Board of Censors reviewed the film. A contemporary Spanish newspaper condemned the film as “...the most repulsive corruption of our age... the new poison which Judaism, masonry, and rabid, revolutionary sectarianism want to use in order to corrupt the people.”

Synopsis

The film consists of a series of tightly interlinked vignettes, the most sustained of which details the story of a man and a woman who are passionately in love. Their attempts to consummate their passion are constantly thwarted, by their families, by the Church and bourgeois society in general. In one notable scene, the young girl passionately fellates the toe of a religious statue.

In the final vignette, the place card narration tells of an orgy of 120 days of depraved acts (a reference to the Marquis de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom) and tells us that the survivors of the orgy are ready to emerge. From the door of a castle emerges the Duc de Blangis, who strongly resembles Christ, with his long robes and beard. When a young girl runs out of the castle, the Duc comforts the girl, before taking her back into the castle. A scream is heard and the Duc emerges again, his beard mysteriously vanished. The film suddenly cuts to its final image, with the scalps of the women flapping in the wind on a crucifix, accompanied by jovial music. It has been suggested that this, along with scenes of violent expression earlier in the film as the lovestruck protagonist is manhandled along by two enforcers, may suggest that the film's message is that sexual repression, whether propagated by civil bourgeois society or by the church, breeds violence. This scene is alluded to in the opening sequence, which is an excerpt from a short science film about a scorpion. There we are informed that scorpions have five prismatic articulations, culminating in a sting.

Here you can watch the first part of the film:

In the final vignette, the place card narration tells of an orgy of 120 days of depraved acts (a reference to the Marquis de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom) and tells us that the survivors of the orgy are ready to emerge. From the door of a castle emerges the Duc de Blangis, who strongly resembles Christ, with his long robes and beard. When a young girl runs out of the castle, the Duc comforts the girl, before taking her back into the castle. A scream is heard and the Duc emerges again, his beard mysteriously vanished. The film suddenly cuts to its final image, with the scalps of the women flapping in the wind on a crucifix, accompanied by jovial music. It has been suggested that this, along with scenes of violent expression earlier in the film as the lovestruck protagonist is manhandled along by two enforcers, may suggest that the film's message is that sexual repression, whether propagated by civil bourgeois society or by the church, breeds violence. This scene is alluded to in the opening sequence, which is an excerpt from a short science film about a scorpion. There we are informed that scorpions have five prismatic articulations, culminating in a sting.

Here you can watch the first part of the film: